How should people of faith be towards the world? How should we build ‘ramps’ instead of ‘walls’?

This is often a favourite question of mine and this talk by David Brooks is such a gift. Yes, sometimes it takes a Jew to tell Christians how to be better Christians in our culture. This talk is one of the best, most challenging, most encouraging things I’ve heard in a long time. Here is a favourite excerpt:

He [Joseph Soloveitchik, the great rabbi, in his 1965 book “Lonely Man of Faith.”] said we have two sides to nurture, which he called Adam One and Adam Two, which correlate to the versions of creation in Genesis.

Adam One is the external résumé. Career-oriented. Ambitious. External.

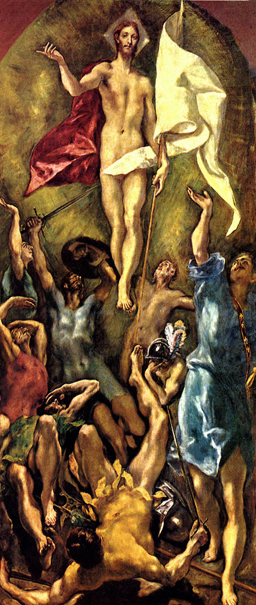

Adam Two is the internal Adam. Adam Two wants to embody certain moral qualities to have a serene, inner character, a quiet but solid sense of right and wrong, not only to do good but to be good, to sacrifice to others, to be obedient to a transcendent truth, to have an inner soul that honors God, creation and our possibilities.

Adam One wants to conquer the world. Adam Two wants to obey a calling and serve the world. Adam One asks. “How things work?” Adam Two asks, “Why things exist and what we’re her for?”

Adam One wants to venture forth. Adam Two wants to return to roots.

Adam One’s motto is “Success.”

Adam Two’s motto is “Charity. Love. Redemption.”

So the secular world is a world that nurtures Adam One, and leaves Adam Two inarticulate.

The competition to succeed in the Adam One world is so intense, there’s often very little time for anything else. Noise and fast, shallow communication makes it harder to hear the quieter sounds that emanate from our depths.

We live in a culture that teaches us to be assertive, to brand ourselves to get likes on Facebook, and it’s hard to have that humility and inner confrontation which is necessary for a healthy Adam Two life.

And the problem is that I have learned over the course of my life that if you’re only Adam One, you turn into a shrewd animal whose adept at playing games and begins to treat life as a game.

You live with an unconscious boredom, not really loving, not really attached to a moral purpose that gives life worth. You settle into a sort-of self-satisfied moral mediocrity. You grade yourself on a forgiving curve. You follow your desires wherever they take you. You approve of yourself as long as people seem to like you. And you end up slowly turning the core piece of yourself into something less desirable than what you wanted. And you notice this humiliating gap between your actual self and your desired self.

So this secular world may look like Kim Kardashian and vulgarity, but I am telling you it is a river of spiritual longing. Of people who are aware of their shortcomings and lack of direction and in this realm.

They don’t have categories, they don’t have vocabularies, but they know the gap.

They know the gap because none of us gets through life very long without being knocked to our knees either in joy or in pain. And a bunch of activities expose the inadequacies of an Adam One life.